Hot off the press

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released their most recent report in August 2021. What are the implications for South African agriculture? By Jorisna Bonthuys.

Recently an assessment of our planet’s future was performed by the IPCC — Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change — the United Nations body tasked with examining climate science.

The IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report clarifies that global warming to date has changed many of our planetary support systems. Some of these changes will be irreversible for centuries and millennia to come.

For the purposes of the nearly 4 000-page report, 234 climate scientists scrutinised 14 000 peer-reviewed studies. Their conclusion was that it is indisputable that human activities are causing climate change, making extreme climate events — including heatwaves, heavy rainfall, and droughts – more frequent and severe.

The findings of the IPCC should serve as “a serious wake-up call” according to one of the lead authors of the report, Prof. Francois Engelbrecht of the University of the Witwatersrand’s Global Change Institute. Engelbrecht was speaking at a media event held online in August this year, and during an interview afterwards.

“Earth is warming faster than previously thought, and the window to avoid catastrophic outcomes is closing,” he cautions. “We still have time to respond, but the world needs to act fast and decisively.”

The IPCC report estimates that warming of 1.1°C has already occurred. This value is perilously close to the thresholds of 1.5°C and 2.0°C that define dangerous climate change. The report further warns that we are likely to cross the 1.5°C threshold in the early 2030s.

“This is a sobering finding,” says Engelbrecht. “It means that we are probably already living in the first 20-year period that will have an average temperature of 1.5°C above the pre-industrial temperature.”

Be ready for heat and drought

With every 0.5°C of global warming, there are clear increases in the frequency and intensity of many types of extreme weather events. The IPCC report states that climate change, including changes in extreme weather events, can already be detected in every region of the world.

“Every bit of global warming matters,” explains Engelbrecht. “Increases in extreme events will be substantially larger at 2.0°C compared to 1.5°C of global warming.”

Southern Africa is warming drastically, at about twice the global rate. Already water-stressed, the region is projected to become even hotter and drier — some of the worst drying that is projected globally will occur in Southern Africa. This increases the risk of three- to five-year droughts.

“When a hot and dry region becomes hotter and drier, the options for adaptation are greatly limited,” says Engelbrecht. These projections do not bode well for agriculture. There are, for instance, major concerns about the effects of climate change on maize production and livestock farming in Southern Africa.

“There is a risk that the industries around cattle and maize – our staple crop in the region – may completely collapse at 3.0°C of global warming, which means about 6.0°C of regional warming,” says Engelbrecht. “The possibility of drastically warmer conditions applies to the scenario of low-mitigation climate-change futures where we reach 3.0°C or 4.0°C of global warming somewhere in the second half of this century.”

Stormy weather ahead

The IPCC report is a rich resource for understanding the complex physical processes behind climate change. It shows how the frontal systems that bring our winter rainfall are shifted towards the South Pole more often as the planet warms, leaving cities like Cape Town vulnerable to drought.

“The relevance for us is that the cold fronts that are so important for our winter rainfall will find it increasingly difficult to reach the southern parts of South Africa in a warmer world,” explains Engelbrecht.

The projections point to continued warming and more frequent temperature extremes and heatwaves. Even where rainfall remains similar or slightly higher, conditions will be drier due to higher evaporation rates. Greater competition for water resources, coupled with higher irrigation water demand, are also on the cards. At the same time, more frequent days with heavy rainfall and risk of localised flooding are likely.

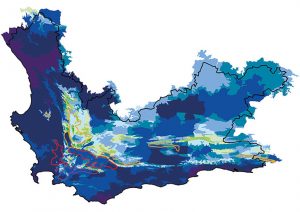

So far, the strongest warming trends are seen over the drier western parts of South Africa (the Northern Cape and Western Cape), in the northeast (Limpopo and Mpumalanga, extending to the east coast of KwaZulu-Natal), as well as in Gauteng.

Warming, shifting rainfall patterns, and more extreme weather events already occur, and are forecast to increase in key agricultural areas, including the most high-yielding fruit production regions in the country.

The Western Cape has, for instance, experienced a significant rate of temperature increase – approximately 0.2°C per decade recorded during 1931–2015 at several locations. Daytime maximum temperatures have increased steadily, as have extreme warm events.

Shifts in rainfall patterns have also been observed, as illustrated by the severe drought of 2015–2018 in the Western Cape. This event was three times more likely to occur because of the human influence on climate.

While climatic challenges have always existed, the scientific consensus is that climate change is a threat multiplier that increases the likelihood and severity of extreme weather events. Some changes to the climate system are irreversible. However, others could be slowed or even stopped by limiting warming.

“In order to slow or stop this process, we need climate stabilisation,” says Engelbrecht. “This requires strong, rapid, and sustained greenhouse-gas reductions, and will necessitate significant adaptations, including in the agricultural sector.”

“Failure to achieve immediate, rapid, and large-scale reductions in greenhouse-gas emissions will destroy our chances of limiting warming to 1.5°C,” cautions Engelbrecht. “We now need to both halt the current rate of warming and ensure adaptation to and resilience against climate change.”

For more on the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report visit www.ipcc.ch.