Paardekloof

Maximising returns on investment. By Anna Mouton.

“To earn more money, you need to put more apples into the export market,” says Willie Kotze, technical adviser with Dutoit Agri. “You’re not going to win by trying to cut costs.” The establishment cost of an orchard is a once-off, and after that production costs will only go up with every passing year.

The Orchard of the Future at Paardekloof aimed to increase Class 1 pack-outs by planting at high density on dwarfing rootstocks. “The purpose was to plant a hectare so that we can learn from it. So that commercially, as an industry, we don’t make unnecessary mistakes,” says Kotze. “We’ve succeeded in that goal.”

A decade of data

“This orchard is what we thought the future would look like, thirteen years ago,” says Kotze. “It would have been planned in 2007.”

The orchard was established in 2010 with Rosy Glow on MM.109 with M.9 EMLA interstems. Trees were spaced 3.5 by 1.25 metres. Conventional planting distances at the time were 4 by 1.5 metres. A conventional Rosy Glow orchard on MM.109 without interstems was planted at the same time as, and right next to, the Orchard of the Future, for comparison.

According to Kotze, the main reason for using MM.109 with M.9 EMLA interstems was lack of confidence in the performance of M.9 under South African conditions. The received wisdom was that our climate is too warm and our soils too poor for M.9.

“The other nice thing about the interstem is that, if you don’t have a lot of M.9 available, you can make a large number of trees quickly,” adds Kotze.

M.9 delivered in terms of precocity, with the orchard yielding 16 tonnes per hectare in the second leaf and 53 tonnes per hectare in the third leaf. “The harvest in the third leaf was way too much,” says Kotze. “Then, in their fourth and fifth leaf, the trees didn’t grow at all.”

The high early tonnages led to stunting and basal dominance. Subsequently, the trees were pruned heavily to remove large branches and encourage growth. This worked — the trees filled their space — but short-term fruit production was sacrificed.

One of the goals of the Orchard of the Future was a total cumulative production of 300 tonnes by sixth leaf. The trial orchard at Paardekloof achieved only approximately 175 tonnes per hectare. “So on paper the orchard doesn’t look great, not least because we also accidently over-thinned the fruit one year,” confesses Kotze.

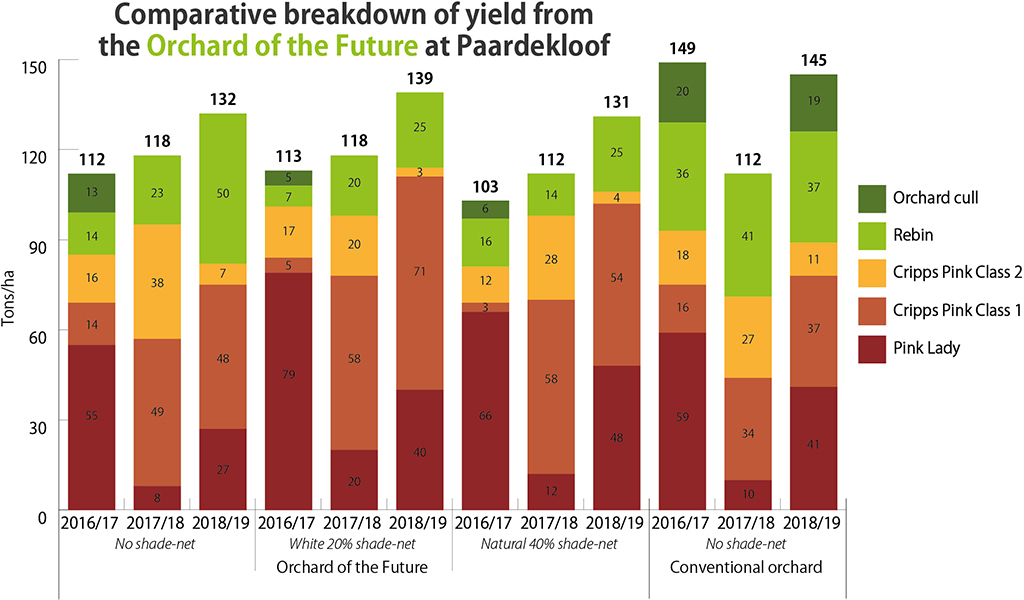

But it’s worth mentioning that the conventional orchard only produced 149 tonnes per hectare by its sixth leaf, and that its first harvest, of 21 tonnes per hectare, only occurred in its third leaf. Since 2017, on average, the Orchard of the Future has produced 116 tonnes per hectare per year, compared to 126 tonnes per hectare for the conventional orchard.

Quality not quantity

Fruit production at Paardekloof is impacted by both sleet and sun. In addition to the fallout from overcropping, the Orchard of the Future was also set back in its third leaf by sleet. Putting up shade nets to protect both trees and fruit was the obvious solution.

The orchard was divided into three sections in 2014. One section was covered with white 20% shade-net, and another with natural 40% shade-net. The third section was not covered, and acted as a control. Kotze stresses that both nets only effectively provide a shade factor of about 10%.

From 2017 onward, when the orchard came into full production, apples from the shaded sections have consistently suffered less sunburn than fruit from either the unshaded section or the conventional orchard. The nets also protected the fruit from sleet damage.

“We were always worried that the fruit wouldn’t colour well under the nets,” says Kotze. “But I think we’re over that. Sure, the fruit won’t colour if the tree is too dense. But with an open canopy, there’s more than enough light under a white net, and we have very little sunburn or damage due to sleet and wind.”

Data from 2017 shows that 73% of fruit harvested from the section of the Orchard of the Future under white 20% shade-net were in the Class 1 Pink Lady category, compared to 53% of the fruit from the unshaded section, and 47% of the fruit from the conventional orchard. These differences have become smaller, but the shaded section of the orchard still yields more Class 1 fruit than the unshaded section and the conventional orchard.

“Many people say that they don’t want to plant under a net, because it’s too expensive,” says Kotze. “I say it’s too expensive to plant without a net. If you start with an expensive, high-density system, and you don’t achieve better pack-outs, because you didn’t protect your fruit, you’re worse off than you were when you planted a conventional orchard.”

Change for the better

The Orchard of the Future at Paardekloof was all about learning, highlights Kotze, not about making as much money as possible. “When this orchard was in its sixth leaf, we were already planting commercial orchards differently. We already knew much more, and we’re still learning.”

One change has been the widespread adoption of M.9, without an interstem. Planting distances are shrinking, and new trees are spaced 0.8–1 metre apart. Kotze states that they are also exploring other options, such as double-leader trees and Cornell-Geneva rootstocks. He believes that these rootstocks may offer an advantage on replant soils, or on difficult sites where soils are too sandy or poorly drained.

“The number one thing is that an orchard has to be under a net,” asserts Kotze. “Therefore, the rootstock has to be something that we can put under a net. We can’t continue farming with vigorous rootstocks. We need greater precocity, smaller canopies, and better colour.”

The Orchard of the Future still has semi-permanent branches, but Kotze explains that simpler tree architecture is preferable. He would rather see renewal of the bearing branches in high-density plantings. A simpler pruning system demands less from the labour force and their managers. However, you need to choose a system and stick to it, says Kotze. “Because someone needs to do the work, and that person isn’t a horticulturist, or as informed as you are.”

What’s the next future?

Kotze worries that people will take the wrong message from the Orchard of the Future at Paardekloof. “Commercially, this orchard didn’t make money as it should have done. In the next twenty years it will make lots of money, but for someone who wants a quick return on investment, this looks like a big risk. The sums don’t work on paper.”

Expensive mistakes were made during the early years of the orchard. “Initially we just had to try to get a tree,” says Kotze. “Then we had to figure out how to prune it. Then we finally achieved our first 100 tonnes per hectare. But after successive harvests, the pack-outs were no better than on a conventional orchard. So we had to figure out how to improve that.”

Lessons learnt have enabled the team at Dutoit Agri to model the performance of high-density plantings compared to conventional plantings, with and without shade nets. A high-density orchard breaks even about a year later than a conventional orchard, due to the higher establishment costs. Nets likewise increase establishment costs. So why plant at high density under nets?

“You won’t suddenly make a leap to producing 60% Class 1 fruit just by planting at higher densities,” says Kotze. “There are a lot of things you need to get right, and the net is the magic factor.”

The Dutoit Agri model looks at various outcomes. Assuming that no nets are put up, and the orchard is never exposed to sleet, the cumulative profit of the conventional orchard outperforms the high-density orchard by around R450 000.00. Add nets to the high-density orchard, and it beats the conventional orchard without nets by around R850 000.00, thanks to better pack-outs.

The model includes scenarios where sleet causes damage during three years in the lifespan of the orchard — all too realistic in Ceres. Under these circumstances, a high-density orchard under nets will have a cumulative profit of just over R6 million per hectare by year 25, compared to about R4 million for a high-density orchard without nets. In contrast, a conventional orchard would have a cumulative profit of less than R5 million.

Kotze is not about to gamble on good weather for the lifetime of an orchard. He supports a more proactive approach. “We know that quality tonnes are the only thing that will save our industry. If you produce a hundred tonnes, do you want to export 40 of those tonnes, or do you want to export 65 of those tonnes? It’s an easy sum to make.”

Image: Willie Kotze.

Supplied by Anna Mouton.

Summary

Table 1 The Paardekloof Orchard of the Future at a glance

| Year established | 2010 |

| Rootstock | MM.109 with M.9 EMLA interstem |

| Scion | Rosy Glow |

| Cross-pollinator | Royal Gala |

| Spacing | 3.5 x 1.25 metres |

| Training | Solaxe |

| Size | 1.05 hectare |

| Trees per hectare | 2286 |

| Nets | Fixed. Part 20% white and part 40% natural. |

The past and present orchard team

Eric Conradie

Nigel Cook

Carel Cronje

Pierre du Plooy

Linde du Toit

Willie Kotze

Hannes Laubscher

Johan Visser

Bonus: The Paardekloof financial model

The technical team at Dutoit Agri generated a financial model of cumulative profit for various orchard systems. They used data from the Orchard of the Future as well as from other operations within Dutoit Agri. The model compares a conventional 4 by 1.5-metre orchard; a 3.5 by 1.25-metre orchard on M.7; and a 3.5 by 1-metre orchard on M.9. A fourth option models the impact of shade nets on the 3.5 by 1-metre orchard on M.9.

For the options without shade nets, the model calculates two outcomes. One is cumulative profit assuming no losses due to sleet. The other is cumulative profit assuming losses due to sleet in years 7, 15, and 23 of the orchard’s lifetime.

The greatest cumulative profit results from the M.9 planting under nets. In contrast the poorest performer is the same planting, without nets, assuming sleet. The take-home message? High-density plantings are costly to establish. The additional investment can only be justified if these orchards produce higher tonnages of Class 1 fruit — for which a shade-net is essential.

Model assumptions

- Cultivar is Rosy Glow.

- Annual inflation of 5%.

- Annual increase in Rands per tonne income of 3%.

- Interest on initial capital not factored in.

- Establishment costs, production costs, annual yield, annual income, impact of sunburn, and impact of sleet based on data from Dutoit Agri and the Orchard of the Future programme.

- Full production yields are 110 tonnes per hectare for conventional orchard, and 90 tonnes per hectare for M.7 and M.9 orchards.

Full production pack-out assumptions

| Orchard | Orchard run% | % Class 1 | % Class 2 | % Class 3 |

| Conventional

No shade nets |

80 | 40 | 40 | 20 |

| M.7 and M.9

No shade nets |

90 | 50 | 40 | 10 |

| M.9

Shade nets |

90 | 65 | 25 | 10 |

| All orchards

No shade nets + sleet year |

80 | 20 | 40 | 40 |